The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of Crew Rotation

Proponents of rotational positions cite burn out and the prediction of future crew shortages as rationale for adapting the concept. As in any transition, there are obstacles and drawbacks to altering a standard.

Yachting is a great career with enormous potential for advancement, a generous salary, and a well- traveled life. The most often heard complaint is the personal life compromises that must be made in order to maximize career growth and salary. The concept of rotational assignments has been heralded as the solution for crew to stay aboard and still meet personal obligations and goals. The idea has merit for some positions, but is not the solution for all personnel issues on a yacht.

As engineering became more complex and the market need expanded, engineers were sought from the commercial sector, where there is a tradition of rotation. Since there was market demand (engineers with broad based experience were a hot commodity) and the premise was well established from the commercial market, the concept gained a toehold in yachting. Other senior crew who had industry tenure and family obligations ashore began to express interest for rotation to be extended to other positions - Captain, Chef.

The concept is not completely new. Freelancers have made a career of stepping in for crew during periods of training, family leave, illness. A freelancing career was the traditional way for crew to balance personal life and spend time ashore while creating a “back-up” plan for yachts.

Expanding the pool of candidates in engineering roles represents the good of the rotation concept. Adapting the commercial concept of rotation was a win-win for yachting. The expansion of the labor pool may have augmented the knowledge base in the engine room, and great engineering can create operational economy aboard. Crossover commercial engineers enjoyed a pay bump up and established yacht engineers benefitted from additional down time.

Since engineering does not have daily interface with owners and guests, the change in crew can be invisible to those aboard – whether owner or charter guests. Not without hurdles, the adaptation of rotation still has engine room detractors. Colleagues in the engine room are rarely exactly equal in skill sets, creating friction. Even with additional procedures and attention to checklists, any lack of continuity is potentially dangerous.

Broadening the model to the position of captain is the bad of the rotation concept. Commercial rotations do not sync with the seasons of yachting. On either a privately used or chartered vessel, the Captain is the face and the force of the yacht. The personality of the captain sets the style of communication, drives the staff selection, and establishes the team dynamic aboard. Even relief coverage by the first mate can alter the dynamic of the team. Long tenured captains have a personal relationship with the owner and understand the owner’s objectives for the program.

When the position of Captain rotates, individual distinctions become secondary to checklists and measurable skills. Along with diminishing the central role of the captain, the responsibilities of the yacht begin to shift from captain to the management company – the one constant in a rotating crew.

When does the rotation theory get ugly? The way to a guest’s heart is through their stomach. Any change in chef initiates reaction. The most frequent complaint of charter guests? The food. The assessments of what was wrong runs the gamut: too fancy, too basic, too rich, too bland. It would seem that if a replacement chef has adequate knowledge of preparation, menu planning and provisioning a change should be seamless. However, all the knowledge and skill is secondary to how much the owner or the guests enjoy the menu. When those aboard are not delighted with the dining experience, feedback and requests are generally presented too late to deter the sense of dissatisfaction.

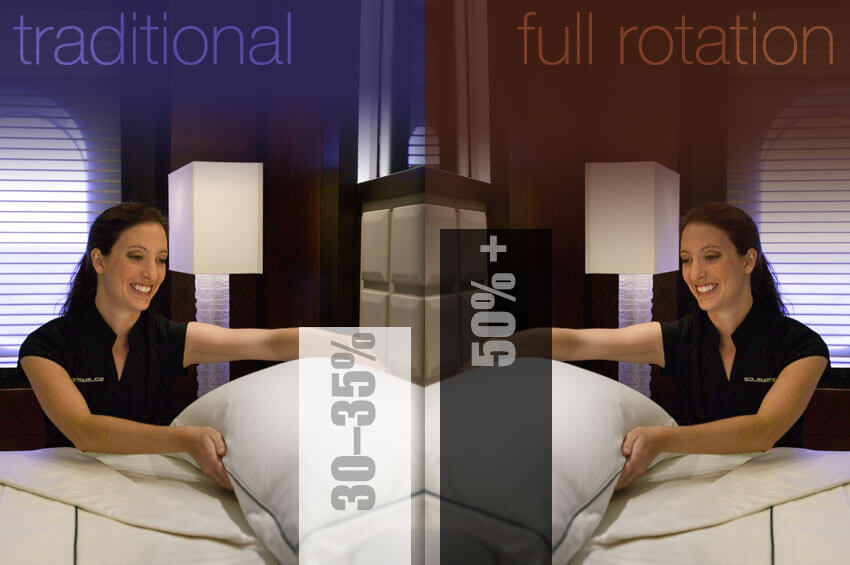

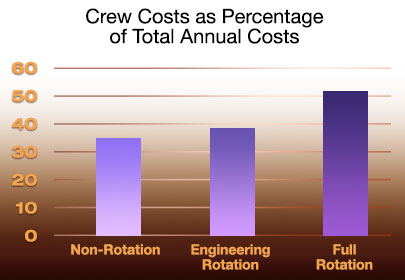

The financial impact of applying the rotation model across all positions is significant. Even when crew is willing to accept a decrease in annual salary in order to convert to a rotational position, the costs to the owner increase. Using cost models like the Luxury Yacht Group cost calculator projects the costs of crew at about 30-35% of the annual operating budget. A fully rotational crew without any decrease in annual salary would shift the cost of crew to over 50% of the operating budget. That represents a significant increase in budget dollars for a yacht owner. Is the owner realizing an equivalent increase in the traditional allures of yachting? They have not enjoyed an increase in the level of service. In fact, the experience of yachting may have been diminished by personality changes and unfamiliar crew.

The financial impact of applying the rotation model across all positions is significant. Even when crew is willing to accept a decrease in annual salary in order to convert to a rotational position, the costs to the owner increase. Using cost models like the Luxury Yacht Group cost calculator projects the costs of crew at about 30-35% of the annual operating budget. A fully rotational crew without any decrease in annual salary would shift the cost of crew to over 50% of the operating budget. That represents a significant increase in budget dollars for a yacht owner. Is the owner realizing an equivalent increase in the traditional allures of yachting? They have not enjoyed an increase in the level of service. In fact, the experience of yachting may have been diminished by personality changes and unfamiliar crew.

Yachting is not universally considered a career path. To some extent that is because people come ashore after a certain age to meet family and personal obligations. Rotation could alter that pattern, but there are downsides to the universal application within the yachting industry. Many of the traditions and the positive appeal of working in the industry will be removed with adaptation of the rotation concept throughout the crew. What differentiates one vessel from another is the experience for owners and their guests. The most important qualities of yachting – delivery of luxury service and creation of a magical experience – are not enhanced by the introduction of rotation.

Sales

Sales

Charter

Charter

Management

Management

Crew

Crew

About Us

About Us

Contact Us

Contact Us

Newsroom

Newsroom